So far in our worldbuilding series on creating fictional worlds, we have figured out what map projections to use and created some basic continents. In this article, we are going to put them together to see how latitudes and placement of continents affect how climate manifests on the world we are building.

Basic Climate Model

Before we start worldbuilding the climate, we need a basic climate model. Climate zones are driven by atmospheric circulation. The sun heats the surface of the earth unevenly. This will be true of any globe. The sun is overhead at noon at the equator, at least at the spring and autumn equinoxes.

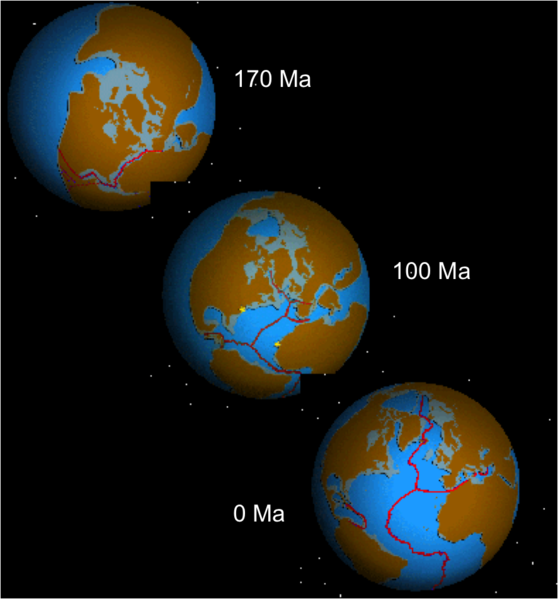

With the sun overhead, the surface of the planet gets heated at the equator more than it does at higher latitudes. This causes warm air to rise at the equator, pulling in cooler air at the surface. The air tends to sink at about 30° latitude, falling back to the surface. this creates a cycle of air being lifted at the equator and pulled from 30° latitude back to the equator. This is called a Hadley Cell after the scientist who first described it.

Additionally, the air at the poles is cold, so it sinks, creating another cell of circulating air between 60° and 90° latitude. This is the Polar Cell, named for obvious reasons.

The final cell is the Ferrell Cell, driving air circulation at mid-latitudes between 30° and 60° latitude. This is a weak cell, so the air circulation in these temperate latitudes is less uniform.

These cells create low and high pressure zones at the latitudes where air rises and falls. Rising air creates low pressure as the air mass is stretched. Sinking air creates high pressure as the air mass is pressed down by sinking air.

High and Low Pressure Zones

As a result of these atmospheric cells, we get zones of high pressure at about 30° latitude and at the poles, and low pressure at the equator and 60° latitude.

High pressure zones are associated with low humidity and clear, sunny skies. Low pressure zones are associated with clouds and precipitation. This means we get arid zones at about 30° and the poles. We also get wet weather at 60° and the equator. The area at the equator is called the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITC).

If your world has seasons, these zones will move north and south throughout the year. The poles of the earth are not perpendicular to the plane of the solar system your planet lies in. This means the sun is overhead at noon in the northern hemisphere at 23.5° N (The Tropic of Cancer) at the spring equinox. The area between 23.5° N and 23.5° S are called the tropics. For your world, you can vary this somewhat, but too great a variation will cause either wild seasonal swings or no seasons at all.

Another factor is climate change. As the planet cools or warms over geological time, the polar zones will move to lower latitudes, expanding ice caps. The high pressure zones at 30° become drier in warm cycles and moister in cool cycles. You can explore this phenomenon when designing your own world.

Prevailing Winds

Based on our discussion of cells of air circulation earlier, we can see how they would create winds at the surface that are fairly uniform. However, the planet’s rotation will defect the prevailing winds toward the west. This is called the Coriolis Effect.

The Coriolis Effect also tends to cause the winds to rotate, causing cyclones in the low pressure zones. These cyclones are areas of even lower pressure than the surrounding area. Winds rotate around them as the cyclone moves across the latitude. More on that later.

Where trade winds converge in the ITC, there is the phenomenon known as the doldrums, or areas of little wind. Tropical cyclones usually form around the autumnal equinox when the doldrums are farthest from the equator.

Applying Continents to the Map

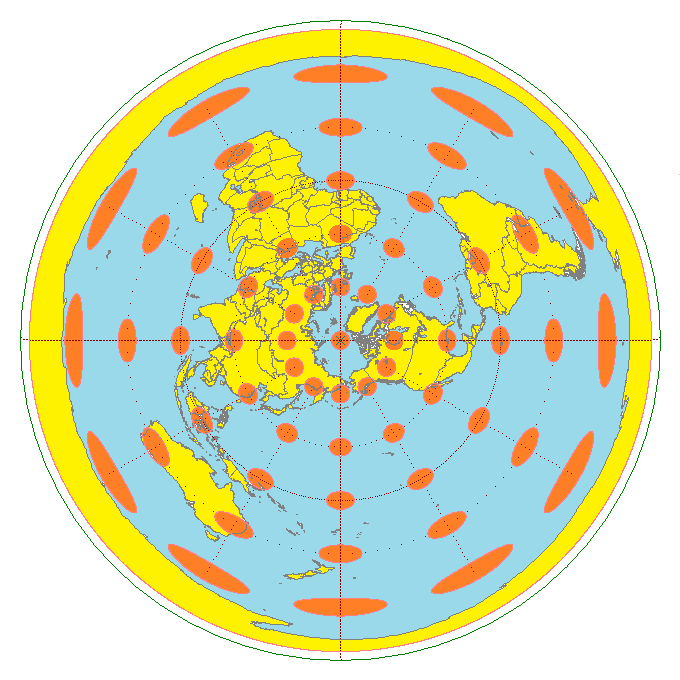

At last, we get to see what our continent looks like on a map. I only plan to use a portion of the continent as a setting for my fictional world, but I want the continent to span a wide variety of latitudes. It will stretch from the sub-polar to the equator. This means I need to use more than one map projection. I will use three different projections and stitch them together.

At the equator I’ll use an Equirectangular Projection. This has minimal distortion between 10°N and 10°S. In the mid-latitudes, I will use an Equidistant Conic Projection. Distortion is least between 20° and 60°. The least distortion is around 40°. At the poles, I’ll use an Azimuthal Equidistant Projection centered at the pole.

Stitching them together is a bit of a cheat, but we end up with an area like so:

Needless to say, this map still has some areas of distortion, but I have tried to minimize it.

Adding the climate zones from our basic model above:

Next, we add the continent. I added a volcanic island in the middle of the spreading ocean similar to Iceland. I can imagine all sorts of story ideas to go along with this island. We’ll start to see the possibilities as we progress.

Now we have a world with bands of desert, grasslands, and forest on a pair of continents with plains, hills, and mountains. But we aren’t finished.

Effect of Continents on Climate Zones

Once we have the continents placed they also affect climate. Because the oceans trap heat more than solid land, large land masses create high pressure zones and large water masses create low pressure zones. This expands the high pressure zone over continents around 30° and expands low pressure zones over oceans at 60° and the equator. There is also the phenomenon of Thermal Lows that affect climate, bringing monsoon rains onto the continent.

Cyclones

The tropical cyclones I mentioned earlier bring moisture from the ITC to higher latitudes. These are hurricanes and typhoons. They generally form over tropical seas at about 10° latitude around the autumnal equinox. High heat and humidity around the doldrums cause thunderstorms that spin due to Coriolis force. These thunderstorms merge into a larger cell.

Such tropical storms move from east to west across the ocean, picking up energy over warm seas. In the northern hemisphere, Coriolis effect causes them to turn right, moving north at about 20° N. The effect is the opposite in the southern hemisphere. These storms bring high levels of moisture to the eastern margin of continents.

On our new world, cyclones might form to the east of the continent beyond the map or in the mouth of the spreading sea. They will move westward across the warm sea, gaining strength and moisture. They will eventually moving north around the central island and bring moisture to the southern edge of the continent in late summer where there would otherwise be a desert. That central volcanic island now has tropical jungles. I think a good name for the eastern part of the sea would be Sea of Typhoons. It’s starting to look like the setting for King Kong.

Also, certain local conditions will affect climate. Mountains trap moisture and are cooler at high altitudes. This will create forests at the northwest of the continent where mountains have formed. These mountains are high enough and close enough to the poles to create glaciers.

Hills and mountains also disrupt prevailing winds. Disturbed air in these regions increase precipitation. Large inland lakes will also moderate climate, increasing moisture and cooling adjacent deserts or warming adjacent polar areas. We don’t have any large inland lakes yet. That’s a topic for my next article.

The Final Map…So Far

Now our worldbuilding has created climates. I added some more detail based on the Köppen climate classification. Köppen’s system is complex enough to cover a wide variety of climates. You don’t need to get as detailed as this. You could simply identify forest, plains, and deserts. The advantage to using this system is that you have a reference to know just how those areas play out at different latitudes and locations.

This Is a Lot of Work. Do I Need to Do All This?

My worldbuilding process gives you a map with a lot of different environments. If you want a desert setting, you have one to the west. If you want a tropical setting, you have one to the south. The eastern part of the northern continent is similar to eastern North America, which is in turn similar to Europe. There is a wide variety of environments to choose from. At the same time, it is limited by certain parameters I set in my head.

This does not mean you are limited by those parameters when worldbuilding. Think about what happens if you tweak any of those parameters. If you diverge from any of the rules I have laid out so far, you can set a story in a world where the rules don’t work as expected. This is the essence of fantasy. For example, in N.K. Jemisin‘s Broken Earth trilogy, the geology of the world is altered by magic. Once you understand how these processes work, it is easier to build a world that still works even if you break the rules.

Why Follow This Process?

Why is it important to know how continents move, how climate works, and what kind of plants and animals live in certain areas? Because as much as culture is determined by ideas, culture is also determined by environment.

It seems like an obvious thing to say, but our environment affects how we think about the world. Keep this in mind when going through the worldbuilding process. Remember that the goal of worldbuilding isn’t just to have a world, but to develop stories, whether they be novels, movies, or games. We are creating a setting, but characters live in the setting and are affected by their environment and culture. Many of their choices might be determined by those factors.

The advantage of having a complete and robust world is that you will already have an idea of how your characters will react to the world around them without having to think it up on the fly. You can move them from place to place and know whether the new setting is something they recognize or is completely foreign to them.

Up Next

We have one more topic to cover before populating the world and creating cultures. In my next article, I will talk about biomes (flora and fauna), mineral resources, and landforms created by climate.

Comments closed