It may come as a surprise to anyone who has read The Statue of the Mad Caliph that I don’t have a map in the book. Many readers of fantasy want to have a map to orient themselves with where in the world the characters are.

I decided early on not to put a map in the book because I didn’t want to give away the history of the world and how it got to be. Rather, I wanted people to focus on what was happening in the story. By putting enough description of the physical world, I hoped readers could figure out where they were in the world.

Maybe it was the right decision, maybe not. I know some readers that don’t normally read fantasy were confused and asked for a map. The problem with a map is that it tells as much about the world as the story itself does. This raises the issue of how much to put on the map.

How I Created My World Map

Some writers don’t need to have a map for their story or are OK with just using one drawn quickly and for the purpose of the story at hand. I’m not like that. I like doing things from scratch. I make my own noodles for lasagne or chicken soup. I grow my own pumpkin for pumpkin soup or pumpkin bread.

I drew the map of my world long before I thought of using it as a setting for a novel. Let’s call the world Yerpik, because I did. The name is actually a portmanteau of Yupik and Earth. The reason will become obvious eventually.

Plate Tectonics

The world of my novel has its origins in a plate tectonics project I did shortly after graduating from college mumble-mumble years ago. I had a keen interest in geology back then and wondered what geological trends in plate tectonics would result in if fast forwarded a couple hundred thousand years or so.

I covered a globe with paper, cut it along continents, and moved the continents to where I thought they would be. It wasn’t a very scientifically rigorous experiment, but I did learn a lot, including dredging up high-school trigonometry after 4-5 years of zero math classes. For some reason, the University of Washington did not have any math requirements for social science majors.

At the time, I was much more interested in sociology, geography, history, economics, and politics than any hard STEM courses. I avoided engineers, science, and math, which is too bad. I would have been a great engineer.

Be that as it may, my college course work prepared me for world-building in detail.

World-building for Dungeons and Dragons

I played a lot of Dungeons and Dragons when I was a kid. The people I played with usually switched between being dungeon master and player. Soon, it was my turn to be DM. I needed to come up with adventures and a setting to play them in.

When we first started playing a teenagers, we would draw a dungeon, fill each room with monsters, and let the players go room to room killing the monsters and taking their stuff. This is the essence of D&D, killing monsters and taking their stuff. After a while it gets boring and players like to have a little context for the dungeon, the monsters, and the stuff. This is where story comes in.

Soon, we matured enough to put the dungeon in a region with a nearby town. Then the town had to be in a country on a continent in a world. Some of my friends liked drawing maps. Every new adventure with them was set in a new world.

One of my friends wanted to create a world from scratch, starting with a coherent geography of the world rather than something drawn quickly on an 8.5″ x 11″ piece of paper. He said he wanted to start “from brass tacks.”

Mapping a Round Surface to a Flat Map

The plate tectonics project left me with a globe covered with paper and continents that had shifted to different latitudes. That globe traveled with me from place to place for a few years before I started playing D&D again.

My friend’s “brass tacks” comment struck me and had stayed with me. I decided any world I build should be based on as much realism as possible. Looking at my globe, I chose an region to develop.

I settled on an area in the mid-latitudes that could be an analogy to a mediterranean culture. The problem I had was putting this region on a map. How do you get a curved surface mapped to a sheet of paper.

If your world is not based on a round globe, then this process isn’t much of an issue. Anything other than a round planet lies in the area of science fiction or high fantasy. If that’s the case, then ignore this whole post because anything goes.

Back to math.

Map Projections

Needless to say, a lot of thought has gone into the problem of mapping the Earth’s surface over the past couple thousand years. The problem is that, no matter how hard you try, any projection of a curved surface onto a flat map will have some distortion.

The most common types of projections are cylindrical, conic, or azimuthal. Which projection should you use? Each distorts the map in some way, but some are better than others, depending on what you want to show.

For a more humorous take on different projections, check out xkcd.com.

The best approach is to take a small area of the globe and map that. The smaller the better. On the other hand, you need a map that will cover a large enough area for your story (or D&D game). I recommend an area the size of a continent. Africa or Asia might be too large, though a portion of them might work well. Try for an area about the size of North or South America or Europe.

Different projections work best for different areas on the globe.

Cylindrical Projections

The most famous cylincrical projection is the Mercator. On this type of map longitudes are parallel. So are latitudes. That means north will always be oriented the same no matter where on the map you are. But distortion is greater nearer the poles. One inch at higher latitudes covers fewer miles than one inch at lower latitudes. This means that to figure out distances and travel times, you need to calculate based on latitude.

The Mercator projection is very common, but map fans hate it because of the distortion at high latitudes. On the other hand, it is great for marine navigation because any course of constant bearing can be plotted as a straight line.

Because the distortion of the map is least at low latitudes and both longitudes and latitudes are parallel to each other, this is a good projection around the equator. I’d recommend it if you are setting your world between about 20° N and 20° S.

Conic Projections

Conic projections work well at mid-latitudes. There is minimal distortion around about 30° N or S, but higher distortion at low latitudes and near the poles. The greatest distortion is past the equator, so this is a bad projection for a whole globe.

The biggest difficulty is that longitudes and latitudes are not parallel. Latitudes are shown as arcs and latitudes converge on a point somewhere off a map of mid-latitudes. This means that north will not always be in the same direction on a flat map. In smaller regional maps, this is less of a problem.

This projection is best if you are working around 10° to 50° latitude.

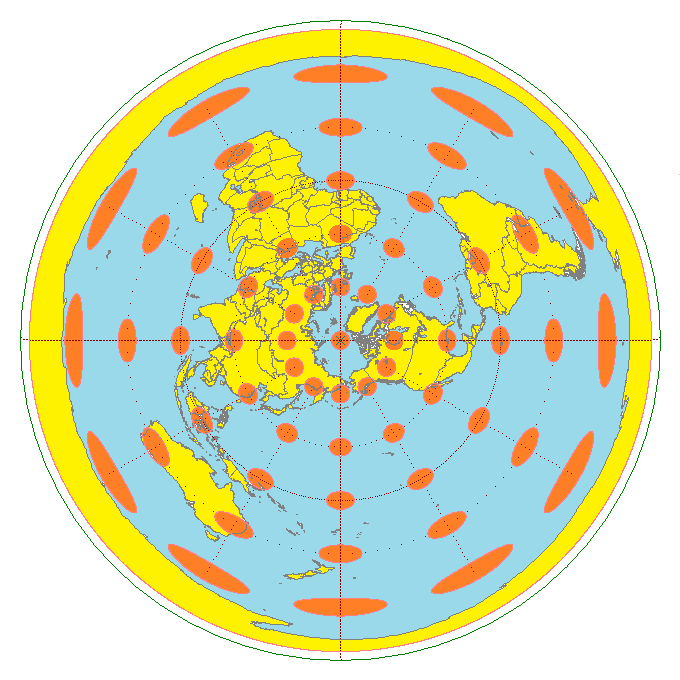

Azimuthal Projections

I don’t use this much because my world has little human activity at the polar regions. Yours might, though. If you create a desert world like Dune, the habitable area might be at the poles, so this projection is worth talking about.

Technically, the azimuthal projection is not limited to the polar, but in areas other than the pole, it has both the disadvantages of the cylindrical and the conic and none of the advantages.

At the pole, latitudes are concentric circles and longtitudes converge on the pole. Because the pole is the center of the map, it is easy to plot locations. You know where north is, and distances near the center are about equal. This projection is best at the center to about 60° above the equator.

This projection shows the opposite pole stretched to infinity. If you want a map of the opposite pole (antipode), you can use this same projection, but from the opposite angle.

Laying out the Map

Once you have chosen the area of the globe you want mapped, lay out the latitudes and longitudes. The polar or Mercator projections are easy, but if you want a good map of a mid-latitude continent like North America or Europe, you will have to plot concentric arcs as latitudes and longitudes converging on a single point. That point will probably be far off your map. Because of the distortion, you probably won’t want to map the area around that point.

This is essentially what I did in mapping Yerpik. It made it difficult to start, but I have a map that has close to equal distances anywhere on the map. I usually only use small areas of the map, so individual maps have north at the top of the page.

I originally used MacDraw on Macintosh Powerbook to lay everything out. Everything disappeared when the computer crashed and I moved to Windows machines. I had printed out a lot, so I scanned them and have been slowly redrawing them using Inkscape.

The advantage of Inkscape is that it is free and open-source. It does pretty much anything I could do in MacDraw or Adobe Illustrator.

Do I Really Need to Do All This?

Probably not. This is a lot more detailed than is needed for a map of a setting for a fantasy novel or game. If you plan on writing new stories with new settings every time, this is not worth the trouble.

On the other hand, if you want a fully-fleshed out world that is internally consistent that you plan on setting stories in for years or decades to come, this is where I would start. In fact, it is where I started. I have set multiple games and stories in this world. They all have the same background, history, politics, and economics. The world is large enough and complex enough that the D&D campaigns and novels don’t cross paths unless I want them to. When writing a new story, I don’t need to worry about the basics. That has been done. I just worry about the details.

In the next post, how to actually draw the physical map of the world.

2 Comments