Last updated on May 26, 2021

When worldbuilding a fantasy world, money and banking might influence how trade is carried out, but it doesn’t actually have much impact on other aspects of a society. For the most part, creating a money system in a fantasy world is a good way to give the world a certain ambience.

What is Money?

The best definition of money I have found is that is a medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value and a method of valuing debts. Most people are familiar with its role as a medium of exchange. Rather than bartering, we put our value in money and use that as a replacement for other valuable items.

Prior to developing money, trade was done by barter. The first forms of money were cattle and grain. Mesopotamians commodified trade by pegging it to the weight of a bushel of grain. Farmers would deposit their grain in the temple, which then recorded the deposit on clay tablets. The temple gave the farmer a receipt in the form of a clay token which they could then use to pay fees or other debts. For more on trade, see my article on Fantasy Economics.

Later, when trade with foreigners required a form of money not tied to the local economy, they developed coins that carried value with it. They stamped metal to indicate its value. Metal is durable, portable, and easily divisible.

Conceptually, any money system depends on the value the users place on the marker being used. The original Mesopotamian shekel represented a certain amount of grain, but the value of gold and silver is all in the minds of the people using it.

The rarity of these items keeps their value high, but their prevalence made them useful as commodities for exchange. The important thing is that there be a stable amount of the material in circulation, otherwise, you run the risk of inflation or deflation.

What Kind of Money?

Societies throughout human history have used a variety of materials as money. For most of history, the material money was made from has been commodity based. People have used cowry shells as money for millennia. The Chinese first started using them 3000 years ago. They were also used in the Americas, Asia, Africa and Australia, and Pacific Islands, often spread by the slave trade.

At various times in history, people have used salt as money, including the “salarium” of a Roman soldier. Ethiopians used it up through the 20th century.

Those of us who played Dungeons and Dragons are familiar with gold, silver, and copper pieces. The first metal money appeared in China in the form of Bronze Knives and spades in China. Though not used as a medium of exchange, the Indians of the Pacific Northwest similarly used large copper plates as symbols of wealth and prestige.

The first coins appeared around the same time in China, India, and the eastern Mediterranean in the 7th century BCE. The Kingdom of Lydia developed the first inscribed coins in the Iron Age. These were of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver. The old school gamers will remember electrum coins from 1st & 2nd Edition Dungeons and Dragons.

Croesus introduced pure gold coins in the 6th century BCE, hence the phrase “as rich as Croesus.”

Money remained much the same, with various reforms, changes in weight, purity, and denomination for the next two thousand years or so until the invention of paper money.

Paper Money

The first recorded use of paper money occurred in China in the 11th century CE. Its development grew out of commercial transactions where exchanging large quantities of coins became difficult. Merchants would give a credit note from a deposit house in exchange for goods. The seller could then take the credit note to draw the amount from the deposit house.

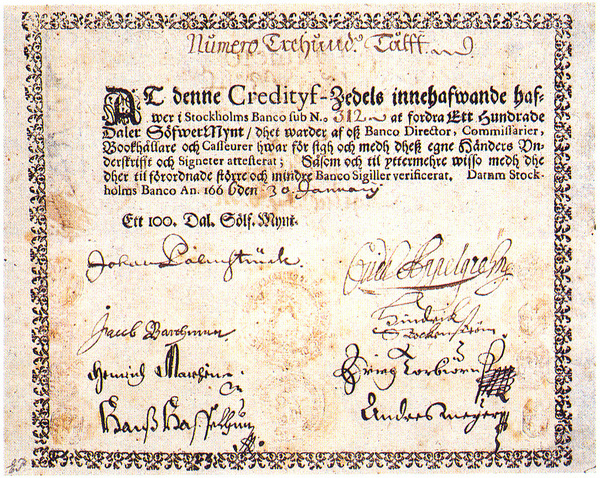

The idea of the paper promissory note made its way to Europe at the end of the middle ages, where trade was flourishing. A merchant could deposit a sum with a banker in one town. In turn the banker handed out a bill of exchange that the merchant could redeem in another town. Over time, these credit notes became bearer notes, that is, they were written to pay whoever held the note.

At first, banks and deposit houses wrote the notes, but eventually, governments stepped in to control the money supply and set a monopoly on printing bank notes.

Paper money carried the fiction that it represented a certain share of gold or silver until 1971 when the U.S. government de-pegged the dollar from gold. Modern money systems have even unlinked value from a specific physical object to a balance on an account sheet, often merely electronically recorded. In the case of cryptocurrency, the currency itself is divorced from a physical form. Could a highly magical society create something like a cryptocurrency?

Money in Fantasy Societies

The easiest way to deal with money in a fantasy story is to ignore it altogether. For the most part, your readers don’t need or even want to know the price of a loaf of bread or a night in an inn. You can simply say that they rented a room or bought a loaf of bread.

If you have your characters counting out coins and making change, your worldbuilding might be taking over your character development. Character first! Worldbuilding gives your characters a background. You don’t invent characters to live in the beautiful world you created.

On the other hand, it might be a useful pressure point on your characters to not have money. This is a great opportunity to follow the old writing advice to force your characters in a corner and poke them with a stick. Lack of money is one way to force them into a corner. If they don’t have money, their options might be more limited in certain situations.

In my own books, I created the fiction that one character has all the money he needs. When he is around, the characters don’t need to worry about money and I, as an author, don’t need to worry about it either. At least inside the story. In another book, I separated them and the one character’s limited money supply is becoming a point of tension for her.

Fantasy Money (Bitcoin anyone?)

If you want to use money to add depth to your fictional world, the easiest method without developing your own monetary system is to use generic coins of gold, silver, and copper or model it on a real-world monetary system such as the English in the middle ages. Kenneth Hodges at the University of California created a list of medieval prices of various commodities and services. It is based on pounds, shillings, and pennies, but includes a conversion to crowns and marks.

If you really want to develop your own fantasy money system, you can go as far as inventing your own denominations for gold, silver, and copper or add other metals such as platinum, electrum, or bronze. You can also follow some of the other historical systems such as cowrie shells or salt.

If you want something truly fantastic, invent some other commodity that has that balance between widespread and rare. It has to be rare enough that it is hard to duplicate easily but widespread enough that it can be held by a large number of people.

One idea might be a magically infused item. Perhaps gold or silver is non-existent in your world. In order to keep a tight control on the money supply, a king might have his vizier or chief mage manufacture items that display a magical image of his face. These might be as simple as a bronze disk or as fancy as a glass ball. I would imagine a glass ball displaying the king’s face would be more valuable than the bronze disk.

Banking and Accounting

Accounting is older than the Bronze Age. It was invented during the late Neolithic as a method of counting agricultural produce. It is closely related to the development of writing. Both arose as a method of counting and recording stores of grain and wealth.

Banking came later, in about the 4th millennium BCE. The history of banking is inextricably linked to the history of money. Temples acted as the first banks in ancient Mesopotamia. People stored their wealth in the temples for a fee. Later, about 1000 BCE, private lending houses arose. The Code of Hammurabi recorded interest-bearing loans.

In Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Greece, and Rome temples acted as banks. In many areas, such as China and India, merchants formed the first banks. Ancient Egypt developed the first government central banks. We must remember that the relationship between the temple and the king was very close in ancient societies.

The signature development of modern banking in the 16th and 17th centuries CE was the issuance of bank debt that served as a substitute for gold and silver. This debt became the new money that underpins the modern international economy.

Banks in Fantasy Fiction

Whatever form banks might take in your fiction, they can also act as useful villains. The best example I have read recently is in Joe Abercrombie‘s First Law and Age of Madness trilogies. The banking house of Valint and Balk acts as a nebulous antagonist that seems to be behind many of the plots and scheming in the books.

Debt can be a motivator for your characters. Like poverty, the fear of poverty and the obligation to pay debt can put a character in a corner. The banker might come by and poke them with a stick from time to time.

Another nebulous entity putting pressure on characters is the Iron Bank of the Song of Ice and Fire series by George R.R. Martin. This bank lends money to governments and armies, often on different sides of a conflict. Much of the conflict in the series is based on how the players scheme to get the backing of the Iron Bank or have to pay them back.

Fantasy Banks and Money in Pancirclea

I am going to skip any development of specific coins in Pancirclea, but I want to have a banking system. This will serve two purposes. My characters can store any wealth they have and borrow money if necessary. Additionally, the bank itself can advance the plot. If characters have borrowed money, the bank can be an antagonist. The characters’ need to pay the debt can force them to act when they otherwise wouldn’t.

I would expect every town to have its own bank. Perhaps they would have multiple lending houses. The most powerful banks would have branches in every city, facilitating trade and enabling traders and adventurers to draw on funds when they are traveling.

I would think the bank would be controlled by a clan, rather than a company. I am leaning toward using clans to control major organizations in Pancirclea. Banking clans, trading clans. Clans that permeate the upper levels of government or the military.

Like the Game of Thrones or First Law worlds, I would have one premier bank that can act as the antagonist in the story. If I need another to put pressure on that main banking clan, I would likely mention another.

In sum (no pun intended), you don’t need money and banking in your fantasy world. You can develop the other features without any detailed development of these features. On the other hand, doing so can enrich the ambient feel of the world and provide some powerful motivations for your characters.