When worldbuilding, politics and government are fundamental aspects of the world you create. How does your character interact with government agents? Are there government agents? Does your protagonist or antagonist have a political view? It’s hard given the state of politics in the United States today to think anyone wouldn’t. As a result, perhaps your characters maintain opposing political views. This might give them the motivation for their actions, thereby creating the drama for your story.

When writing speculative fiction, it is easy to forget about the politics of your world. Lazy writers will default to clichés. Too frequently, mediocre writers set their fantasy story in medieval feudalism. Similarly, futuristic science fiction relies on some form of fascism or universal democracy. Don’t fall into this trap.

History of Politics

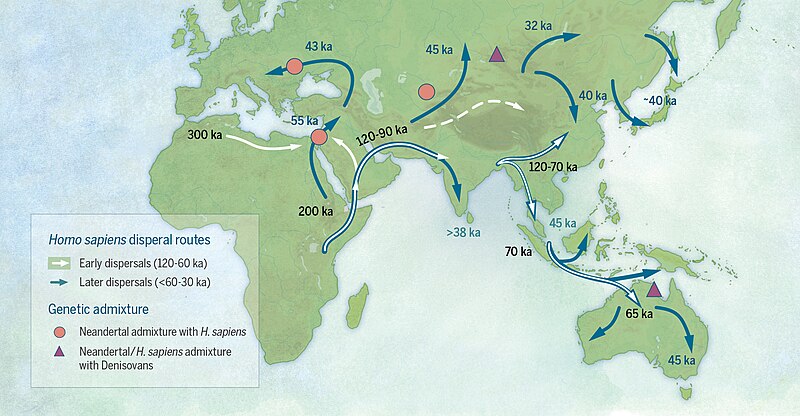

Politics has been a feature of human society since the beginning. Therefore, one must imagine politics and government came long before civilization. Other primates also have forms of social organization. Similar to their primate cousins, paleolithic humans lived with their families in band societies as hunter-gatherers. See Worldbuilding 102 – Caste, Class, and Clan in Fantasy Societies.

The earliest evidence of prehistoric warfare is during the Mesolithic era approximately fourteen thousand years ago. Moreover, with war comes diplomacy. The first evidence of diplomacy was well into the Bronze Age in Egypt. On the other hand, we must imagine some form of formalized contact between tribal bands before that.

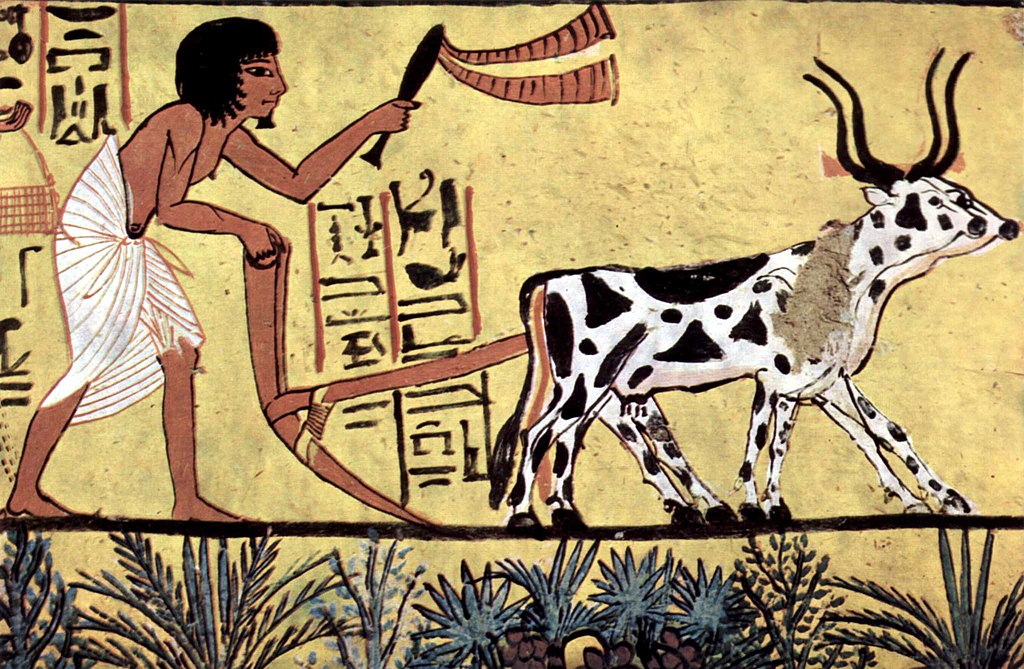

Tribal social organization first emerged in the agricultural revolution, in about the eighth or ninth millennium BCE. The development of agriculture led to higher populations. As a result, denser societies grew in inequality, developing political and social hierarchies.

The first small city-states appeared at the beginning of the Bronze Age about five thousand years ago. Subsequently, by the third to second millennium BCE, some of these had developed into larger kingdoms and empires. See Worldbuilding 102 – Creating Cities in a Fantasy Society.

Some societies created governments based on the tribal structure they grew out of. For example, Rome formalized the tribes that made up Roman society. The words tribune and tribute derive from the Latin word for tribe.

Type of Political Systems

When worldbuilding politics and government, think about the range of possible governmental systems. After all, political scientists since the time of Plato have classified governments into various types. The most familiar are monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy. A monarchy is rule by a single individual. This group includes kingdoms, dictatorships, and tyrannies.

Oligarchy is rule by an elite minority. For example there are the aristocracy, plutocracy, and rule by a racial minority.

Democracy is rule by the people as a whole either through direct or representative democracy. Direct democracy usually involves initiative or referendum. Representative democracy includes republics and parliamentary systems.

On the other hand, anthropologists classify political systems differently.

Uncentralized Political Systems

Uncentralized systems include the band society and the tribe. Band societies consist of small family groups. These are usually extended families or clans of thirty to fifty individuals. See Worldbuilding 102 – Caste, Class, and Clan in Fantasy Societies.

Tribes are generally larger. They usually consist of many families. Typically, tribes have more complex social institutions, including chiefs or councils of elders. In addition, they are generally more permanent than bands. Often, tribes are sub-divided into bands.

Centralized Political Systems

Centralized Political Systems include chiefdoms, sovereign states, and supranational political systems such as empires or leagues.

Chiefdoms are more complex than tribes or band, though they are less complex than a state or empire. Centralized authority is the main feature of a chiefdom. People living in tribes and bands are more or less on the same footing. On the other hand, those living in chiefdoms face inequality. Consequently, a single family of an elite class rules the chiefdom. In addition, complex chiefdoms can have multiple levels of political hierarchy. Small kingdoms, duchies, or other feudal units fall into this category.

A sovereign state has a permanent population, a defined territory, and a centralized government. Also, they have the capacity to enter into relations with other sovereign states. Certainly, this form of government is the most recognized in the modern era, though it was less common in medieval Europe.

Supranational Political Systems

Empires are widespread states ruled by a single person. They can consist of multiple kingdoms or other polities. Some empires included democratic features. Their wealth often allowed them to build city infrastructures. Similarly, their political control maintained order among diverse communities. Such political control often required complex governmental structures.

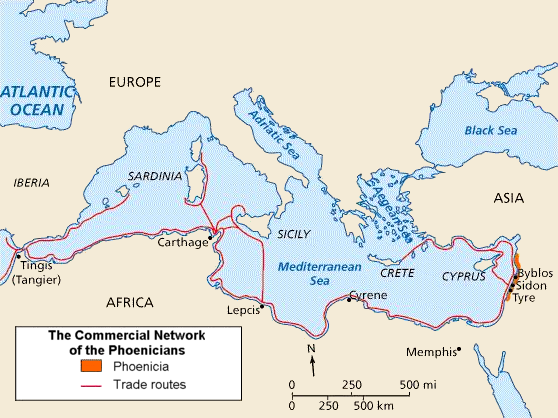

Leagues are international alliances of states with a common purpose. Often, leagues form under military or economic pressures. Often, representatives of all involved nations meet in a neutral location. For instance, the European Union in modern times or the Delian League of ancient Greece are both leagues.

These large categories mask a complex set of governmental types too numerous to list here. Click this link for a list of various types of governments.

Political Divisions in Fantasy Societies

The main benefit of worldbuilding politics and government is having clearly defined political divisions. These divisions are a vast resource to mine for dramatic conflict. Above all, divisions arise from differing views on how best to govern a society. Often, such divisions are ideological. Other times, factions might simply be jockeying for control of resources. Also, reasons for political division overlap. Factions with non-competing views might form larger factions, such as the Republican or Democratic parties in the United States.

In short, to find the political divisions in your worldbuilding, examine the societies you have created so far. Look to economic, class, or religious differences.

Economics and Class

In Worldbuilding 102 – Economics in Fantasy Societies Part 1, I asked whether we need to define economics to write a fantasy story. Certainly, worldbuilding politics and government is where it pays off. Economics is about providing people with the resources to survive or thrive. Consequently, the debate over allocation of resources creates conflict. In the context of a political system, that conflict creates factions.

In Worldbuilding 102 – Caste, Class, and Clan in Fantasy Societies, I wrote that social structures divide people into groups and define a person’s position in society. As a result, these groups tend to share common interests in advancing or maintaining social status. Often, this can be the basis of a political faction.

Religion and Philosophy

In addition, religion and philosophy are basically explanations for how the world works. These world views provide rallying points for political factions you can use in worldbuilding politics and government. For more, see Worldbuilding 102 – Religion and Philosophy

After all, ideology is a powerful political motivator. Anyone growing up in the 20th century recognizes the power of political ideology in the conflict between communism and capitalism. Similarly, in ancient times rulers claimed authority from the will of god or the gods. This was true in pagan Rome, Christian Byzantium, China, Egypt, and most other ancient civilizations.

Any difference between groups of people can form the basis of a political faction. The strength of a faction might depend on how deep and pervasive those divisions are. For instance, differences in race or language might form the basis of a faction. See Worldbuilding 102 – How To Make a Constructed Language Sound Natural for more on language. Also, see Worldbuilding 102 – Creating Societies in a Fantasy World – Demographics for more on race.

How Rulers Rule

In Rules for Rulers, CGP Grey laid out the actual mechanism through which rulers apply political power. Rulers gain power and maintain it by balancing the needs of key supporters, no matter the type of government. Grey used an argument fromThe Dictator’s Handbook. The ruler achieves political balance by implementing three basic rules.

1. Get key supporters on your side,

2. Control the treasure, and

3. Minimize key supporters.

“No matter how bright the rays of any sun king: No man rules alone. A king can’t build roads alone, can’t enforce laws alone, can’t defend the nation or himself, alone. The power of a king is not to act, but to get others to act on his behalf, using the treasure in his vaults. A king needs an army, and someone to run it. Treasure and someone to collect it. Law and someone to enforce it. The individuals needed to make the necessary things happen are the king’s keys to power. All the changes you wish to make are but thoughts in your head if the keys will not follow your commands.” CGP Grey.

The application of these rules in a given situation could form the basis of a good political thriller, whether modern, historical, or fantasy.

Worldbuilding Politics and Government in Fantasy

As I have said many times, the core of a good story is the drama created by conflict between characters. Politics is a gold mine for conflict and drama, especially the politics of personal relationships.

I have laid out a number of potential political conflicts within a society that might lead to political factions. Now comes the time in worldbuilding your politics and government to decide how to apply them.

Features of Pancirclea Society

In my demonstration world of Pancirclea, I applied demographics, settlement patterns, urban geography, magic and technology, and some economics. I defined three cultures in Worldbuilding 102 –Applied Worldbuilding. Later, I focused on the Savannah culture (Töpfumaar Daaškhōhu).

The source of magic among the Töpfumaar Daaškhōhu is human sacrifice. Consequently, the central feature of their society is human sacrifice and slavery. They might take slaves from among their own people. More often, they will go to war or raid the Silvans to capture slaves. In addition, Hillfolk will trade slaves for grain or other goods.

Social Divisions in Töpfumaar Daaškhōhu

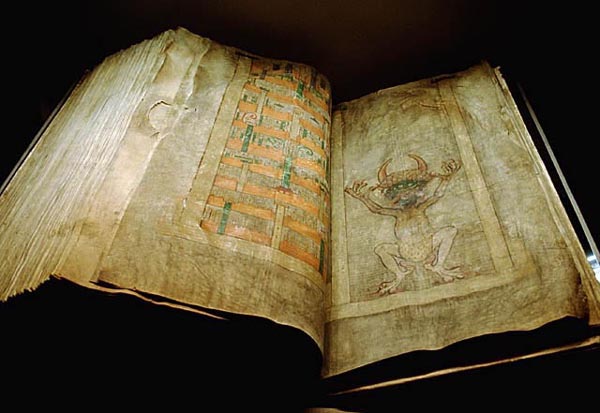

In Worldbuilding 102 – Caste, Class, and Clan in Fantasy Societies, I chose a caste system for the Töpfumaar Daaškhōhu. There are four castes: warriors and rulers, scholars and priests, merchants, and peasants. Religious rules and sacred texts govern relations between the castes. In addition, there is a large underclass of slaves made up mainly of Silvans. This underclass exists outside the caste system. Only the top two castes of warrior rulers and scholar priests may own slaves and only their owners may interact with them.

Powerful banking and trading clans are members of the merchant caste. These clans profit from the slave trade. In addition, the warrior and ruler caste borrows from banking clans to finance their wars.

The scholar and priest caste supports the entire system by enforcing religious rules. These rules govern the class and caste divisions of their society. This caste includes mages and priests. Both need slaves and ritual sacrifice to cast spells to maintain their power and the power of the ruling elite.

Political Factions in Töpfumaar Daaškhōhu

Now that we have an idea of the social groupings, we can begin worldbuilding politics and government. The outline of the social structure shows a clear conflict between the upper castes and slaves. Being outside the caste system, slaves have no official political power. That power is held solely by the warrior and ruler caste.

That does not mean other groups have no political influence. After all, political influence is often exercised by the application of other types of power. For example, merchants can use the power of the purse to cut off finance from the rulers. Priests can interpret religious rules in the rulers’ favor or not. Slaves and peasants have few political levers other than the potential for revolt and revolution.

Governments and States in Töpfumaar Daaškhōhu

I named six cities in Worldbuilding 102 – Constructed Language for Fantasy Fiction – Words:

Čönkög̲ōn

Köbaškhōmör

Gōndoreẖu

Reẖuzoẖu

Anzoreẖu

Qaaqdeẖuškhōmör

Čönkög̲ōn is central and among the oldest of cities. Furthermore, it is the site of the main temple of the religion. The temple is similar to an Aztec pyramid, with an altar at the top for the gathered crowds to view the ritual slayings.

Political rulers need to be near the base of the religion. After all, the source of their political authority derives from sacred texts maintained by the caste of priests. Čönkög̲ōn therefore is the central and most powerful city of the region.

As a result, the king of Čönkög̲ōn has extended his political control over neighboring cities, creating the Töpfumaar Empire. He conquered Köbaškhōmör and Anzoreẖu in war. In addition, he subjugated Reẖuzoẖu in a one-sided alliance. Furthermore, ambitious members of the warrior and ruler caste gravitated to the imperial court from these cities. Over time, this caste created a byzantine and ruthless bureacracy.

Qaaqdeẖuškhōmör and Gōndoreẖu maintain independent kingdoms due to the wealth and power derived from their slave trade. However, the political elites of all neighboring cities struggle to maintain their political autonomy in the face of the power of the imperial court in Čönkög̲ōn.

Potential Political Conflicts

In laying out the social structures of Körung̲ung̲éẖu (Pancirlea), I identified numerous conflicts that could serve as the basis of a dramatic conflict. All you have to do is place your characters in one or more of the groupings defined. Doing so should provide plenty of opportunity to define dramatic conflict either internally or with or among other characters.

There is the conflict between slaves and their masters. Also, there is the conflict between the various castes of Töpfumaar Daaškhōhu. Mages and priests rely on merchants and warriors for a supply of slaves for human sacrifice. Merchants might oppose war because it disrupts trade while warriors and bankers might support it because it the source of their wealth. The differing views of the merchants and rulers or rulers and priests create constant political conflict.

In addition, there are the social divisions of culture and demographics. Most slaves come from the Silvan culture. There are traders and merchants from the Hillfolk who share a similar but separate caste system.

You can use any or more of these ideas from worldbuilding politics and government as the basis of your story. Use them as a central conflict or as background. I recommend making your world as complex as you can. This will result in more complex characters. See Writer’s Digest (May/June 2021) for a great article on The Russian Nested Doll Theory of Motivation.

As you can see, fleshing out the social structure of your world creates a gold mine for for political and personal conflict. This adds depth to your world. As a result, your readers gain the opportunity to explore a world outside their own, whether to investigate the structure of their own world or as an escape from it.

List of Society Worldbuilding Topics

For reference to previous society worldbuilding topics, use these links.

Human Demographics

Humanoids and Non-Humans

Settlement patterns (Villages, Towns, Cities)

Designing Fantasy Cities (Urban Geography)

Magic and Technology (Resources, Knowledge, Magic)

Economics

Types of Economies and Trade,

Money and Banking,

Caste, Class, and Clan

Language

Sounds and Phonemes

Words and Morphology

Culture

Architecture

Philosophy & Religion

Government & Politics